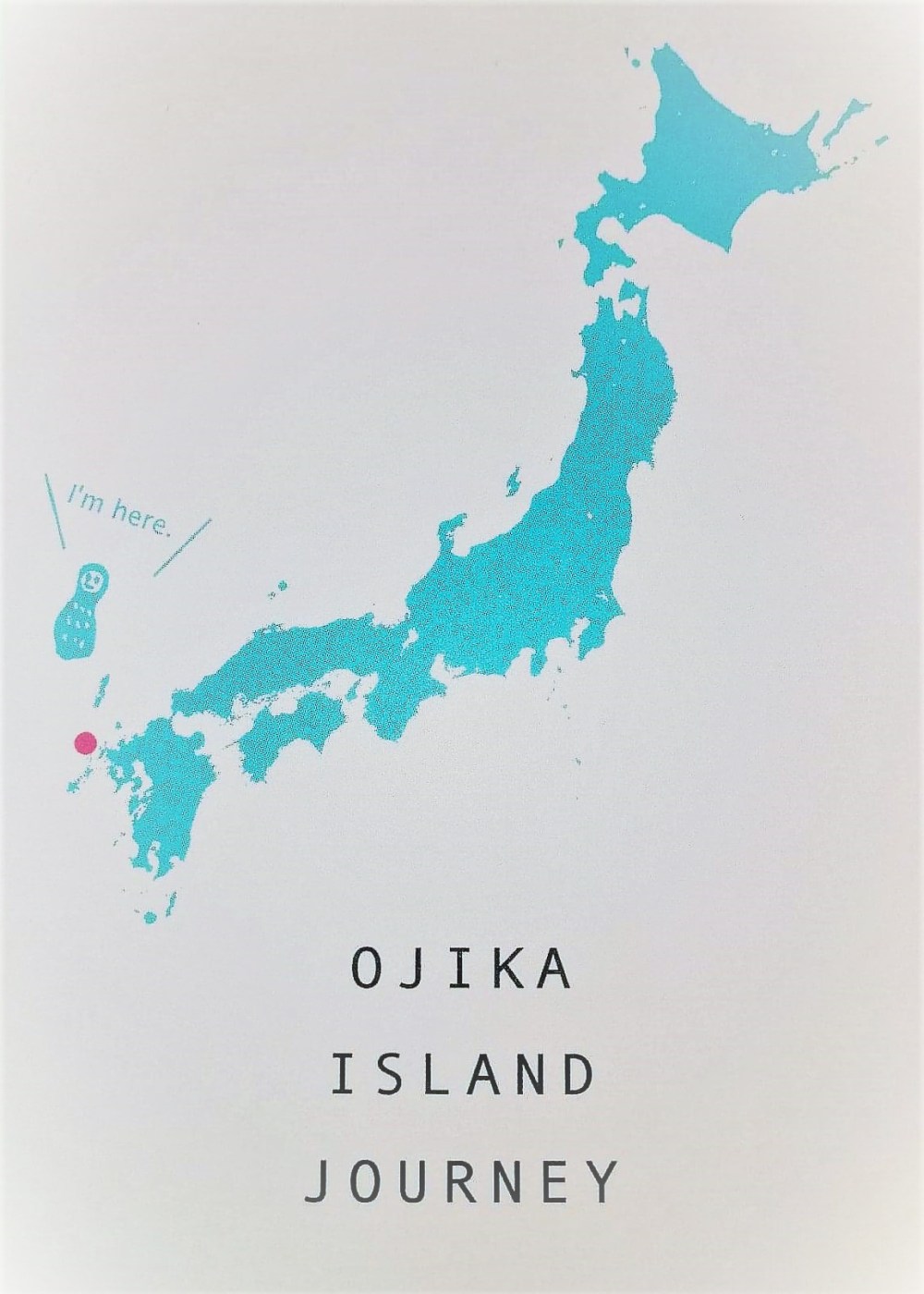

How does one best spend Spring Break in Japan? A month on a remote island off the coast of Nagasaki should be the only answer. I embarked on a Workaway adventure, volunteering a helping hand at a hotel in return for bed and board for four weeks in March. Ojika is in the north of the Goto Islands chain, Southern Japan, closer to Korea than Tokyo. Accessible by ferry from the cities of Fukuoka or Sasebo, the island is small with a population of only 2,500 and is largely self-sufficient. As I crossed the water, the only souls left heading to Ojika were workmen and elderly couples returning from visiting family on the mainland. Ojika is uniquely underpromoted and despite racking the internet for clues as to what might await me, I was taking a gamble on the unknown. Luckily, as soon as I arrived I was embraced with open arms, quite literally, by my boss’s mother and that was the start of my most precious time in Japan to date.

Most importantly, Ojika’s natural scenery is wildly beautiful. Ancient lava-enriched red rock cliffs, secluded crescent-shaped coves, untamed bamboo forests, the high pitched whinnying of black kites circling above the harbour at sunset and an avenue of pine trees that interlace above your head. I’m still enamoured with the place. My favourite afternoon activity was to choose a spot on an old-fashioned paper map and go exploring. I never unpacked my nice clothes as I’d usually end up clambering over rocks or picking my way through woodland to just see that little bit further, what was around the next bay. It was a simple childish excitement and I often had the scraped knees and tired giddy grin to match.

Working at the Shimayado Goen, a traditional family-run Japanese inn and the island’s main hotel was also a pleasure. Belonging to a group is an important aspect of Japanese work culture and despite only volunteering and possessing minimal language skills, I was made to feel valuable. I lived and worked alongside a band of lively European helpers who taught me new card games and the best karaoke tunes. The manager and his family extended their hospitality to everyone and I considered myself thoroughly spoilt. We regularly indulged on grand spreads of freshly caught sashimi and whiled away beery nights in the adjoining karaoke bar. On a breezeless hazy afternoon, the grandparents even treated us to a cruise around the island on their fishing boat. Lone craggy rocks in what seemed to be the middle of the ocean were inhabited by hundreds of perched sea birds.

Compared to living in a major Japanese city, the tiny island has its own rhythms and slower pace of life. Everyone greets each other in the street, old ladies hold hands on their way to the allotment, Edelweiss trills from the loudspeaker system to tell the farmhands it’s lunchtime and skulking cats form furry huddles patiently awaiting leftover fish. I was once caught in a downpour whilst out walking and not only did a passing man gift me his umbrella, apologising as he did for a slightly crooked spoke, but a woman then offered me a lift home in her car too. I met kind but also eccentric islanders; a man that wore pink every day from head to toe and the comedian that dressed up in a costume made of beach trash when a roving art troupe visited. Ojika is as vibrant as it is peaceful.

I’m so grateful to have been a temporary resident of this sanctuary. I’ll be back.